WHO?

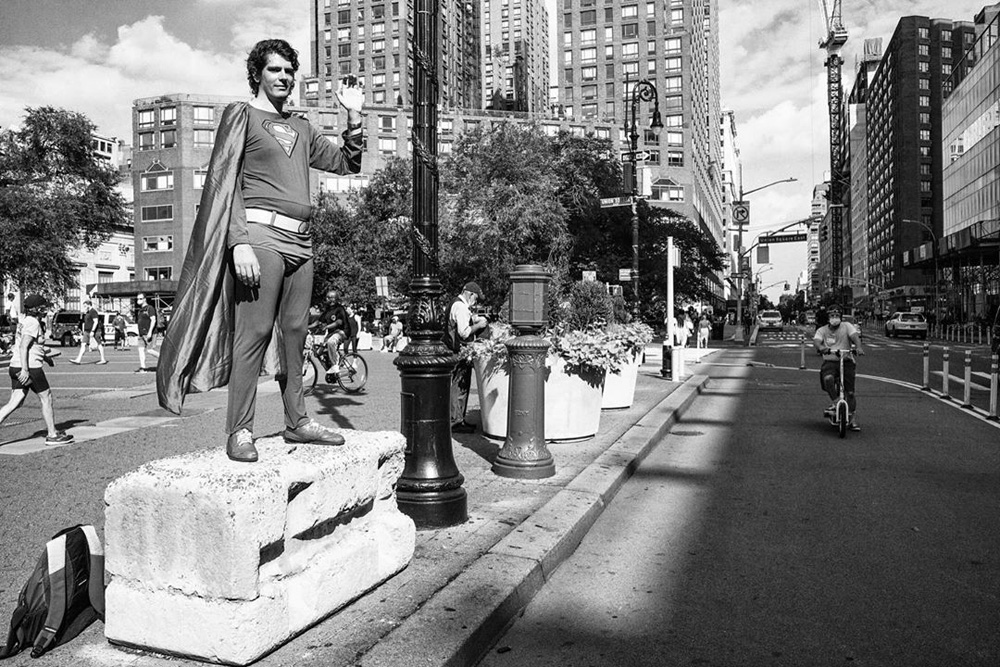

I grew up in a family of classical musicians in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. and in a sense I guess i did follow in their footsteps, but my own path was in rock, punk, and experimental musics. I moved to NYC in 1988 in search of the “authentic” life. D.C. had always felt to me like a transient place that had no real indigenous history or traditions worth paying attention to. It was more museum than melting pot, and everything felt very sanitized and knowable. Arriving in New York, particularly in that time, felt like stepping into a vivid movie that I could be a participant in, as well as a witness to, 24/7. Constant surprises and an endless sense of possibility, change, and discovery were the norm. I remember walking through the loud Brooklyn streets even on my first day in the city, noticing all these little scenes unfolding––conversations, gestures, facial expressions, outbursts, unexplainable occurrences––and in my mind’s eye I would habitually freeze them into little stills, fixing some kind of felt apogee of the experience which stayed in my memory, maybe for only minutes, or maybe much longer, but it amuses me now to recognize that what I was having then was the impulse to photograph. It was almost another 20 years before it dawned on me that I should be taking pictures. I have no idea where that impulse was cultivated. It wasn’t from an interest in photography. I liked photography growing up, but I had always considered it something other people did. Around 14 or 15 years ago I decided it was time to stop saying “I wish I had a camera,” and to start using one. Now photography has permeated every part of my existence, and it seems to be a perfect answer to problems and questions I’ve faced throughout my entire life. For instance…

WHERE?

I resist thinking of myself as a “New York Photographer,” or of the city being my subject matter, but I cannot deny that my practice was formed by living here, and although I have traveled and shot in many other places, New York City is still where the vast majority of my photographic activity happens. I feel sorry for photographers who feel like they have to travel to far off lands to make their work. All I have to do is leave the house. My students often ask me about strategies, or good “spots” to shoot in. Not that I think there’s anything inherently wrong with this approach, but it just isn’t usually my bag. Having a destination or a goal, for me, is only useful in that it gets me out the door, but once I’m out I usually just try to be led by life rather than trying to make it conform to my expectations. I trust that my success at picture-making doesn’t depend on my having “great ideas” or overly determined concepts of “projects.” I think I find more interesting experiences or original work by letting go of all that. Sometimes I’m envious of my peers who can work from a deterministic mission statement, or adherence to a theme or idea of genre, because it seems like it would be so comforting and clarifying. But when I try to work that way I have a hard time escaping my preconceptions. I get inhibited by a sense of obligation to reality, or the idea that I have to to do justice to a “subject,” to illustrate what I think I know, rather than responding honestly to what I feel. When I sit around and think up what sound like good ideas for a photo “project” they later strike me as unoriginal at best, or just laden with careerist notions. I just want to make my own work.

WHEN?

For better or worse when I was very young, maybe only 12 or 13 years old, I internalized an idea that the artist’s life was 24/7. No one told me this was the deal. Somehow, in my obsessive ingestion of music, art, books, movies, performances, and the biographies or articles I read about the makers of them, I assumed the art life as eschewing the boring drudgery of “normal life” which I found so unexciting. As a result, the decades I spent focused primarily on music were often frustrating. It seemed like I spent so much of my time waiting. Waiting to find the right people to work with, waiting to find a space for rehearsals, waiting to get to the venue. Waiting to play. It felt like there was at best a 90-minute period each day where I would get to feel alive, and the rest of the time was basically a drag. Some of my past partners and friends didn’t stand a chance. You had to drag me kicking and screaming into “normal” things. Photography solved this problem for me, not because I’m necessarily practicing it 24 hours a day, but because it’s possible that I could. Street wandering is still the core of my practice, but wherever I am, going to the post office, meeting friends for dinner, taking the cat to the vet…anywhere at any time there could be a picture waiting there for me. So, photography has made me a more patient person, and a better partner and friend, not because I am willing to walk away from my obsession and be “good,” but because my obsession can come along with me. I have erased all separation between art time and ordinary time in my life. I live in the work.

WHAT?

I don’t have any objection to being called a street photographer. It’s certainly a major aspect of my practice and the history of the genre is dear to me. But here’s my problem with the term: as soon as you say “street photography” we think we know what we’re talking about. Our assumptions start flooding in about what the work is or should be about, the intent of it, and what we think the boundaries of the genre are or aren’t. Some of us will think it’s about the process divorced from the appearance of the final image, and others will think it’s about the resulting picture fitting into a model or not. I went through this madness already in my music career. Twenty years of arguments about what was or wasn’t Jazz. Twenty years of us championing the avant garde as being the true continuation of the tradition didn’t change the minds of people who believed the definition of Jazz was, “did it sound like the music of the 1950’s?” I started photographing on the street before I knew there was a genre called street. Then I discovered the masters and felt a temporary sense of belonging. Then I watched over the last several years as people tried more and more to codify “street” into subgenres and knowable objectives. Call me crazy, but I don’t think heroes of mine like Garry Winogrand, Helen Levitt, or Daido Moriyama strove to make great “street photographs.” I think they were engaging with their world, their own questions about it, and were exploring their relationship with the medium. The pioneers of Jazz were too busy inventing it to worry about the rules. Ultimately I want to be like them, to do the real work of the artist, rather than adhere to some notion of fitting into a mold or making photos that imitate approved tropes. Thinking about names seems to ruin everything. My least favorite description of what I am though is when people call me a “professional” photographer. As I tell my students who are hung up on whether their gear or their work is professional enough, the word “professional” just means, “looks like what you’ve seen before.” The fact that I get paid to do photography is meaningless. Since the pandemic, all my hired photo jobs have completely evaporated, and I live entirely off of making my personal work, self-publishing, and teaching online. Not that I didn’t enjoy doing the odd wedding, or musician portrait, but if things could keep going the way they are right now I wouldn’t miss those jobs. Self-publishing has been much more rewarding. Having my photos appear in the zine Hamburger Eyes several times has felt like the kind of success that fits who I really am, much more than my being published in The New York Times.

WHY?

For me it’s all for the purpose of learning and growing. In other words, the same reasons it’s worth being alive. What else is there? More than anything I’m a big believer in the value of daily practice. All the external rewards life offers are impermanent and fleeting. The satisfaction that comes from getting a little recognition, or a paycheck, wider acceptance…even being asked to answer these questions from UP; the satisfactions fade quickly and the lonely, hungry questions and anxieties return like mosquitoes buzzing around my ears. You can’t satisfy an obsession. Practice, for me, is defined by my commitment to do a thing under all circumstances for its own sake. Being out in the world with the camera every day, being present, looking closely at things; it comes with its own rewards. Rewards that last. I no longer walk around feeling apart from everything and everyone as I did as a young person. I feel connected to the organism of city life/human life, and I’m both in it and observing it at the same time. Today I have everything I need to be awake, and to feel alive. Anything else I get is a bonus.