WHO?

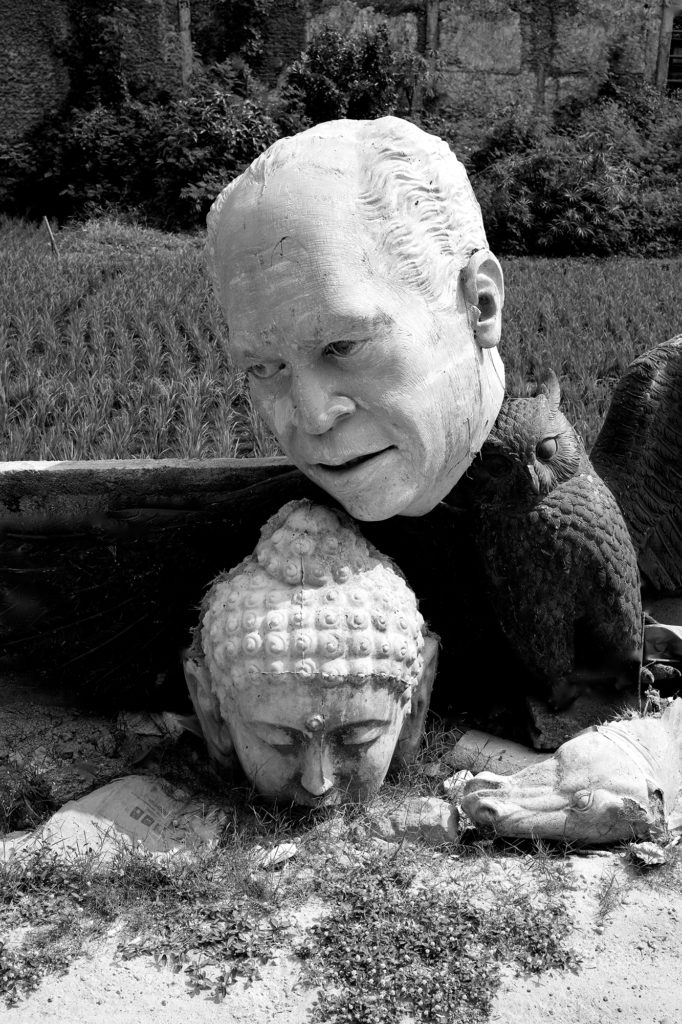

Attila Bartis, writer, photographer. Born in Marosvásárhely (Transylvania, Romania) in 1968, lives in Budapest since 1984, and partially in Yogyakarta (Java, Indonesia) since 2014. Member of the Hungarian Széchenyi Academy of Literature and Art. This (and the list of my books and exhibitions) is the longest CV I have ever written and I would like to keep this habit in the future too.

WHAT?

What I do is clearly not street photography despite the fact that most of my photos were taken outside the studio. The street photographer basically is interested in the interesting, in the moment, in the dynamics of life. And to be able to show this you need some qualities that I don’t have. The life is fast. And I am a slow photographer. If sometimes I am able to see a kind of transcendent order in the world, if my emotions recognize themselves in a shadow or light, if a picture has his own silence, I am already glad.

WHEN?

I got my first camera when I was 9 years old. It was an old Hungarian box camera, Pajtás, from the flea market. With that I shot my first roll of film but for many years that was the last roll too. I used the camera without film, only watching the world through the viewfinder–like how an astronomer uses the telescope.

My father was a poet and a journalist, because of political reasons in ‘84, when the Ceausescu regime became really mad, we had to leave Romania. Already in Budapest when I was 18 I started to write my first novel, The Walk, and almost in the same time I got a camera from my father. I didn’t have a lab, I had no money to pay for the prints, so I used slide film, the East German ORWO was very cheap at that time. So the writing and the photography were present parallel from the very beginning. But the camera I got was fully automatic, I couldn’t control what I did.

In ‘88-89 I had my first trip to West Europa. This period was almost the end of the communist era but nobody knew yet that this was the end. I wanted to emigrate. I spent a time in a refugee camp in Denmark, from there I went to West Germany. And in Hamburg I spent all my money to buy a secondhand manual camera. I had no money left even for bread, I had to come home.

Basically, it is much easier to make money from photography than from literature. But one of the biggest gifts I got in this life was that after my first novel was published somehow I was able to survive with the royalties, grants and prizes that I got as a writer. I studied photography at the academy but I never had to work as a photojournalist or commercial photographer. I could keep my freedom to take the camera in my hand only when I felt that I wanted to do it. What this freedom means is that for 35 years I live together with my camera.

WHERE?

Now, in the last few years mostly indoor, or out of Europa. The western democrat, liberal, ultra-enlightened white people already have so much human rights that slowly you will have to make a written agreement with yourself to have right to take a self portrait. And I hate to fight, especially to fight with the stupidity.

It’s a pity that exactly we, the center of the world, the top of all cultures, the most equal between the equals, exactly we misunderstood so deeply what the freedom means.

It’s a pity that exactly we built for ourselves a world where most of the people are condemned to depression and loneliness. It’s a pity that exactly in my own culture where photography was invented, already I don’t feel comfortable to go out to the street with my camera. I can’t really see what we have won with some of the rights we have today but I see clearer and clearer what we have lost because some of them.

As I remember my grandparents were still glad if somebody took a picture of them. And I also didn’t feel that I lost my freedom nor my human rights nor that I was humiliated if somebody took a picture of me without asking for my signature. So now I feel much better with my Leica out of the western society, between the people who have less rights than us but who are not so depressed and so paranoid like we are.

WHY?

I never will tell you why. Not only because I can’t, but also because already I don’t want to know why. I spent a few decades of my life trying to answer to that elementary question why I do what I do. Why I write my novels, my essays, why I make my photos. (I hope I make them, not only I take them.) And fortunately, a few years ago I woke up. And this helped me a lot. This gave me an extremely big freedom.

I need the food, but I don’t have to understand why my body needs the bread and the water. That is something what a biologist has to know, not me. If I know and I understand at least a small part of the answer that is nice but it will not change my life at all. My hunger, my needs will be the same.

This is with the art too, with any kind of art. For some people to do art is an elementary need. To do art is not a profession, not a passion, it is something much more profound. But you don’t have to know why you have this need. If you fall in love, a psychologist maybe can tell you exactly why it happened. But if you are the one who has the clear answer why you fell in love, there is not love anymore.

Why? Because I love it. This is the most essential answer. All other reasons can be true (I have a lot) but they are secondary, any of them would not be able to force me to take a camera in my hand.