Melissa O’Shaughnessy: Tell me a bit about your background. Where were you born and where did you grow up?

Gulnara Samoilova: I was born in Ufa, Bashkortostan and lived there until 1992. I fell in love with photography when I was 15 years old and knew immediately that it was what I wanted to do with my life. When I finished high school I went to work as a black and white printer. A year later I became a portrait photographer and shortly after got a job as a photography teacher in a Youth Arts Center. I was also working on my own personal projects.

For those of us whose knowledge of Russian geography falls short, where is Bashkortostan? What is the culture like there?

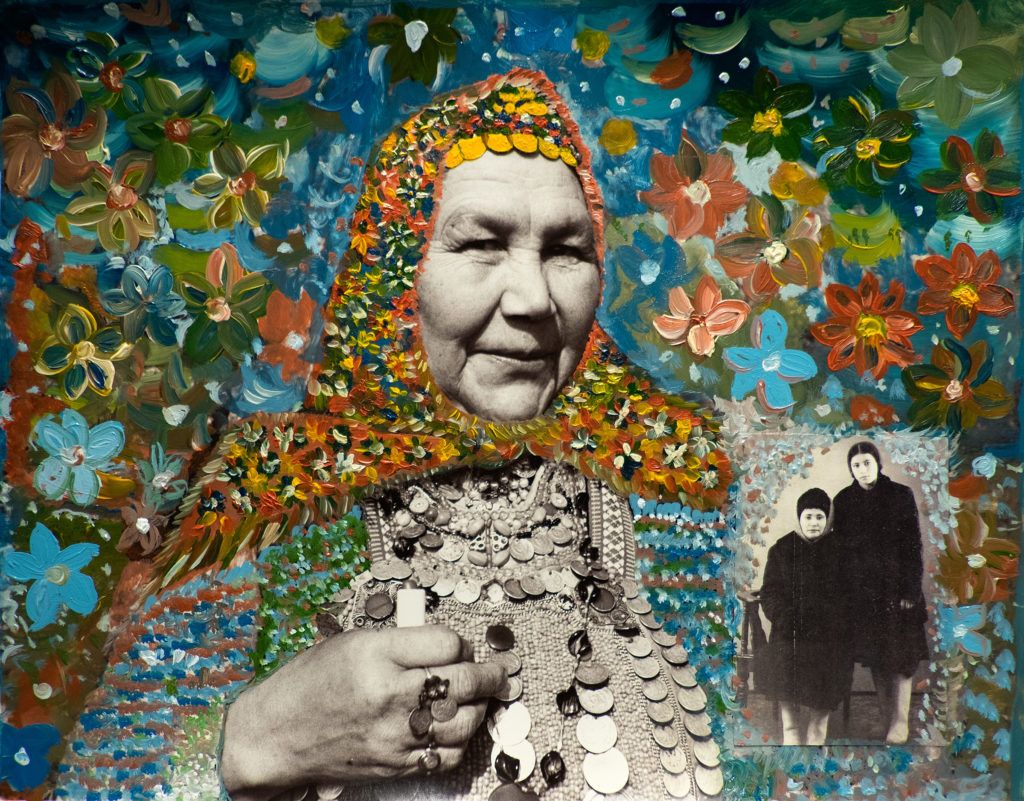

Bashkortostan is one of the autonomous republics within Russia on the outskirts of the Ural Mountains. I am Tatar, which is an ethnic minority in Russia. When I was growing up in the Soviet Union, I wasn’t familiar with my own culture. In 2016, I went back there for the first time in 15 years and had a mixed emotional reaction. I was rediscovering my own heritage, but simultaneously felt like I was robbed of my culture growing up since it was prohibited to celebrate it. A few years ago I was invited by a local photography group to come to Bashkortostan to travel around the republic and photograph the everyday life there. What I found were beautiful, open people, delicious food, gorgeous landscapes, and a rich cultural life full of lively music and jaw-dropping, handmade costumes. Each village could be identified by their own unique dress patterns. I have been going back every year since.

How interesting. Was it Glasnost and the fall of the Soviet Union that allowed the reemergence of the ethnic Tartar culture?

Yes. During the Soviet Union, any celebration of a Tartar, Bashkir, or other non-Russian culture was not popular. My mother even refused to speak Tatar at home with me. After the fall of the Soviet Union various cultures became more acceptable.

You mentioned that before you left home you worked as a photography teacher as well as on your own personal projects. Can you tell me a little about those personal projects? What kind of work were you making?

When I was going to college in Moscow in 1990, I attended an exhibition of Gilbert and George. The images they created were mixed media, large scale, hand-painted prints. For me it was eye-opening. It really inspired me to go in a different direction with my personal work. I was able to express my frustration with what was happening in the Soviet Union at the time through hand-painting my photographs. My photographs explored various issues including the neglected elderly, single mothers, air pollution, and the AIDS crisis. I was one of the first artists in the Soviet Union to mix photography, oil painting, and collage. I was also the only female fine art photographer in Bashkortostan. In addition to that, growing sick and tired of being asked to pose nude for male photographers, I began a project photographing male nudes. This became very controversial in Bashkorkostan, mostly populated by conservative Muslims. I wanted to show male nude photographs in a tasteful and artistic way.

Wow, sounds like you were deeply engaged with photography at quite a young age. Why did you leave Bashkortostan? Did you come directly to the United States?

In 1992 I was one of the organizers of a cruise trip on the Volga River with around 200 international photographers. I had actually almost given up on photography but someone bought two of my photographs on this trip and it gave me confidence to continue my work. I was also one of the 14 emerging Russian photographers chosen for a travel exhibition in the United States. I was invited to attend the opening and just never left!

Was New York your first stop? Why did you end up staying and not going back to Russia? What direction did your photography take at this time?

Yes. I fell in love with New York City and felt a creative freedom that I hadn’t had in Russia. I was able to attend the International Center of Photography school as a full-time student. At ICP I was exploring alternative methods of photography like polaroid transfers, cyanotypes, and continued to add to my black and white nude project as well as hand-painting photographs.

I know that you also worked for the Associated Press. Can you tell me a little about that? What led you from the personal work to being a staff photographer for the AP?

After I graduated from ICP I got a job as a darkroom printer at the Associated Press. That’s where I used my qualifications as a photo retoucher to begin to restore their archive and retouch prints for major competitions such as Pulitzer Prize and World Press Photo. What began as a temporary job as a photo printer became a permanent staff position as a photo retoucher and photo editor for special projects. In addition to restoring the AP archive, I was also working on exhibitions, book projects, and handling the photo submissions for competitions. After covering September 11, 2001 I was offered a staff photographer position, but I quit instead.

How did you go from a retoucher and editor to being out photographing the 9/11 attack? I know you won First Place in the World Press Photo competition for a photo you took that day.

At the time of the 9/11 attacks I was living 4 blocks away from the World Trade Center and when the first plane hit I was asleep and woke up from all the sirens. I turned on the TV and saw the second plane hit. I grabbed my camera and ran to the World Trade Center because I thought that there might not be any other AP photographers there yet. I recognized right away that this was an intentional attack that needed to be documented. Once I got there I was focusing on photographing the injured people that were brought out of the buildings. I was standing across the street when the South Tower collapsed. I fell and got buried with dust and debris. Once I realized I was alive I began shooting again on autopilot. I had no recollection of reloading my film, changing my lens, and photographing. I was in this state of shock when I took the photo that won first prize in the World Press Photo competition.

I can’t imagine how traumatizing that must have been. Is that why you quit the AP when they offered you the job as a staff photographer?

Yes. After 9/11 for the next year I looked through every photo that was taken that day by AP staff photographers and freelancers. That added to the trauma of 9/11. I was forced to revisit the horrific event on a daily basis. This proved to be too overwhelming for me and I didn’t want to be working in the news anymore so I quit a year later.

After leaving the AP, what was next for you photographically? When did you become interested in street photography?

After AP, I went in the complete opposite direction photographically. I started shooting weddings and opened my own wedding photography business. In 2012 I was hired as a personal photographer documenting a family vacation in China. In addition to my professional equipment, I brought along my point and shoot Leica with me, That was when I began shooting street photography for my own enjoyment. It made me realize how much I missed shooting for myself. In 2013 I went to Cuba for a week to shoot street photography and knew that this was what I wanted to pursue. At the same time I realized that i wanted to commit to being a full-time artist and quit doing commercial work.

You’ve cited Mary Ellen Mark as being a big influence. Was it around this time that you first met her?

I was a big fan of her work since the early 90s, when I first met her. I attended her exhibition and book signing in New York City. I had wanted to attend her workshop in Oaxaca, but was always too busy with my business. When I found out she was giving a workshop in New York, I signed up. This ended up being her last workshop as she passed away in 2015. She was a huge influence on my photography moving forward. After the workshop she wrote me an encouraging letter to continue to pursue my photography. She wrote “someone as talented as you really should pursue a serious personal body of work”. I was very insecure as a photographer at that time. When I attended the World Press Photo Awards Ceremony and Exhibition Opening in Amsterdam, I overheard two guys commenting on my winning image. They suggested that it was taken by a passerby who just “happened to be there”. It made me question myself as a photographer. Mary Ellen Mark’s letter gave me the encouragement and confidence to be a full-time artist.

I’m sorry I never got a chance to meet her. She was an incredible photographer and seemingly a wonderful human being. This seems like a good segue way into talking about Women Street Photographers. Tell us about how that started.

I wanted to put together a group exhibition of women street photographers, but I didn’t know any at that time. I began my research on Instagram and slowly started to discover many female photographers from around the world and saving the photos that I liked. That was how I began the Instagram account, @womenstreetphotographers, as a personal catalog for future exhibitions. I didn’t want to just post pictures by women, I felt that it was important to write additional information about the image and provide educational value. In December of 2018 we had the first Women Street Photographers exhibition in New York City which included the work of 75 women from all over the world and a solo exhibition by Gisele Duprez. Since then we’ve had exhibitions in Bulgaria, Poland, Belgium, India, and Malaysia. In December 2019 we had our second exhibition, consisting of 94 women photographers and a solo show by our first artist residency program winner, Valerie Six.

It’s just astonishing how much passion and energy you’ve put into the Instagram account and the shows. Amidst it all, are you able to put time aside for your own photography?

Thank you. I’m very grateful to be able to inspire and elevate other women photographers. Women Street Photographers is my passion. Through it, I discovered myself as a curator. Putting together a show is an art in its own right and is personally fulfilling for me. Every year I go back to Bashkortostan and photograph there for a month. That recharges me and keeps me going. When I teach workshops in other countries I always set aside personal time to explore and take photos.

How do you go about judging and curating the Women Street Photographer shows? What makes a street photograph stand out for you?

I am looking for a story and an emotional connection to a photograph. A good photograph has one of these. A great photograph has both. When I am putting together an exhibit, I always choose a larger amount of photographs than needed. I then make proof prints and see how they look together. I don’t just show a group of pictures. The entire exhibition collectively has to have a flow to it. Sometimes a photograph may not be the strongest, but it fits well within the body of the exhibition. And vice versa. Occasionally I will come across a successful photograph, but it will not fit into the flow of the exhibit.

We’ve touched on Mary Ellen Mark, what other photographers have inspired you over the years?

I mentioned Gilbert and George earlier. Others are Helen Levitt. She was the first photographer whose work really spoke to me when I moved to New York. I look to Alex Webb’s work to help me take more complex and layered photos. Recently I’ve been inspired by Linda Hacker. Seeing her work makes me want to take abstract pictures. When I saw what Valerie Six was able to produce from her New York Artist Residency, it gave me a fresh take on the city and made me grab my camera and shoot in New York more. Meeting so many diverse, talented women during the monthly meetings of Women Street Photographers in New York has been wonderful. I enjoy the sarcastic, dry sense of humor in the work of Ximena Echaque and Sonia Goydenko. I love street portraits by Dominique Misrahi. Their dedication to the art of street photography along with many other women I have met in the past inspires me and gives me the momentum to continue my passion.